THE GOOD OLD DAYS

After becoming Swedish and acquiring free port status, St. Barths experienced a remarkable period of economic growth, characterized by unprecedented expansion The island became a place where ail religions and nationalities could meet and trade freely, weaving the threads of a prosperous cosmopolitan society at the dawn of the 19th century. Despite the challenging circumstances including the seizure of Swedish ships by English and French powers, the constant threat of privateers, the lingering impact of the French Revolution, and the destructive hurricane of 1792 that caused significant loss of life and property in Gustavia with 51 homes destroyed and 26 lives lost, St. Barths continued to welcome new residents who arrived on its shores day after day. lt reaffirmed its role as a bustling commercial hub where diverse cultures intertwine, and promising opportunities thrive.

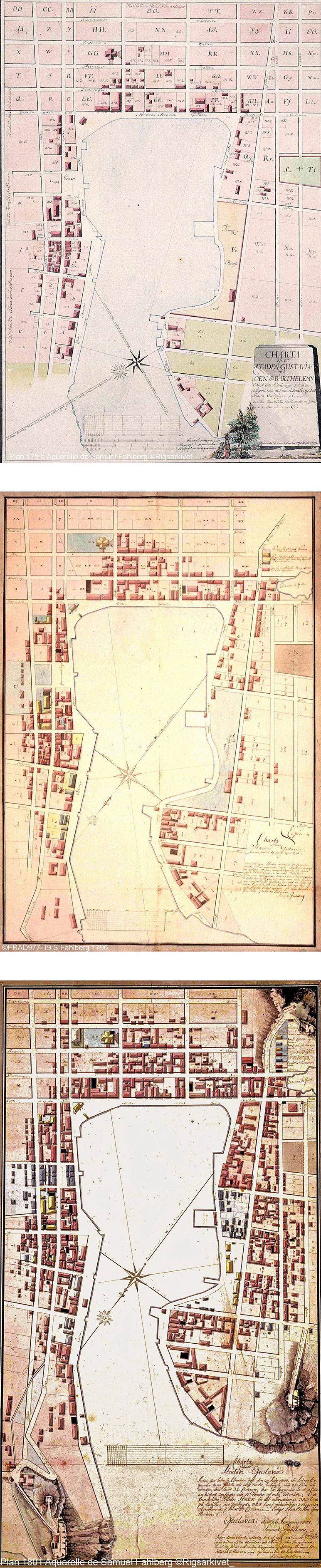

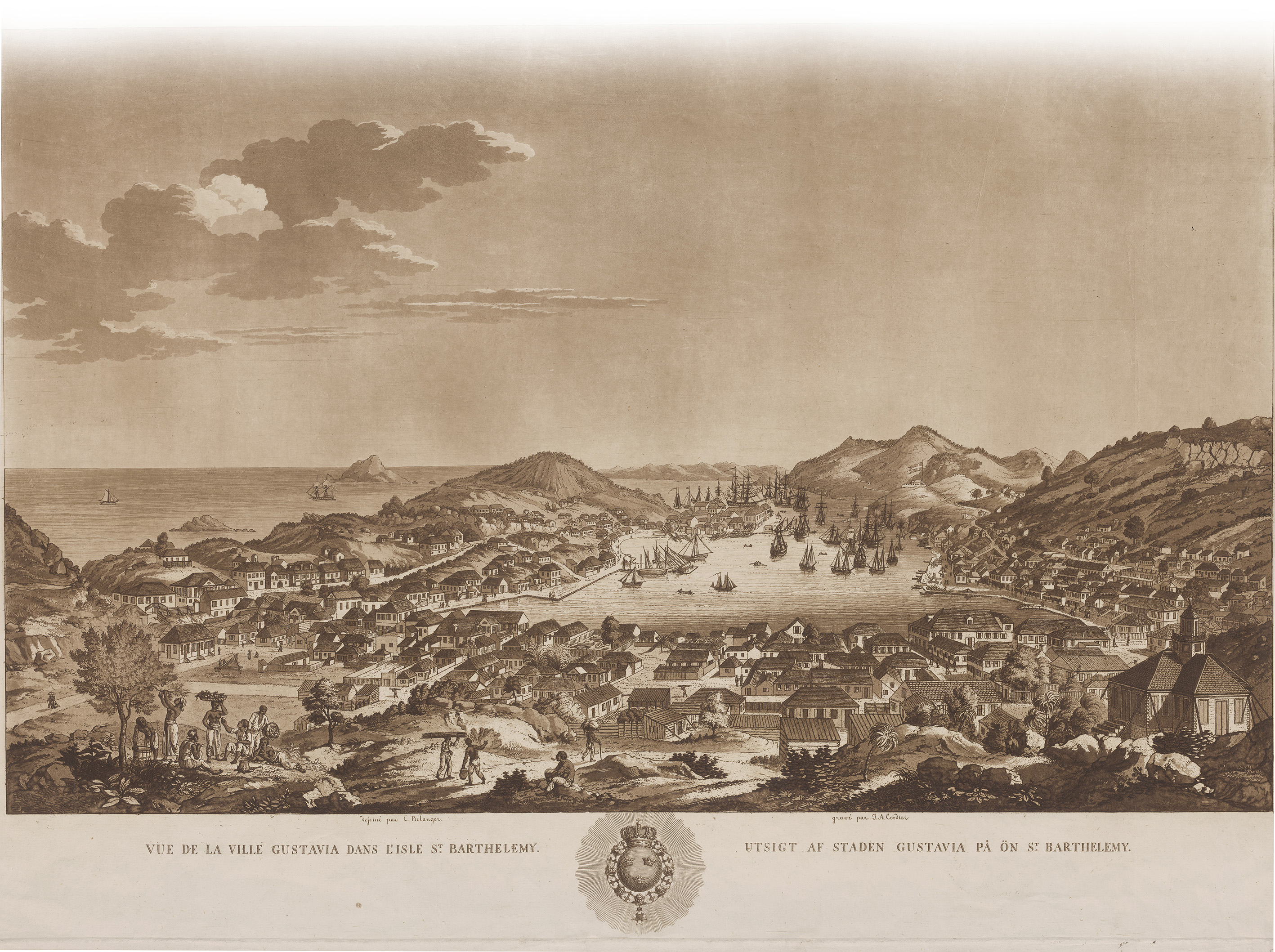

ln 1799, St. Barths recorded exports amounting to nearly 1.7 million piasters gourde, surpassing imports which stood at approximately 336,000 piasters gourde. Gustavia, with its enduring urban arteries, has already cemented its status as a significant city widely acknowledged across the Caribbean region. With over a thousand ships docking annually, the population of the island had grown to around six thousand in habitants by 1800, with nearly five thousand of them residing in Gustavia alone.

On March 20, 1801, Sweden, aiming to maintain its neutrality amid the numerous conAicts engulfing European nations, encountered a predicament when the English Aeet unexpectedly arrived off the coast of Saint Barths, without issuing any declaration of war. Due to its limited military resources, the island was incapable of mounting a defense and reluctantly surrendered to the English, preventing any bloodshed. Following a year of English occupation, during which the initial foundations of an English fort were laid, St. Barths was ultimately returned to Sweden in a dismal condition on July 10, 1802. The Gustavia shipyards experienced a significant reduction in resources due to the extensive felling of Guaiac trees on the island. England, acknowledging the destruction caused during their occupation, agreed to provide compensation amounting to 9,000 pounds. Balthazar Bigard, the French consul at the time, and his descendants pursued substantial claims for compensation, which persisted until the 3rd Republic.

ln 1807, the French launched an attack on St. Barths, employing surprise as their strategic advantage. Although the episode was brief, it served as a reminder to the small colony of their vulnerable military defense capabilities.

ln 1810, Governor Ankarheim found himself dealing with a mutiny that would elevate August Nyman to the status of a hero, while Samuel Fahlberg, one of the most notable Swedes, would unfortunately be branded as a traitor.

ln 1811, an impressive total of 1,793 ships sailed through the port of Gustavia, serving as a testament to the perpetual vitality of this bustling and vibrant place. <<The Report of St. Bartholomew>> holds a significant place in the history of press as the first newspaper ever printed in St. Barths. Established in 1804 by Swedish judge Andrew Bergstedt, it underwent a change in ownership in 1811, when it was acquired by John Allan, a ccfree man of color,>> who continued as its publisher until 1819. Starting in 1827, a fresh weekly publication called <<The West lndian>> emerged, while around 1831, a handwritten monthly publication named cc Gustavia Free Press>> made its debut.

These publications are mainly written in English, whereas daily interactions and activities are conducted in the languages of Molière and Shakespeare. Swedish, except for specific instances like religious sermons, remains less prevalent since the number of Swedes on the island never exceeds 127 individuals •

at any given time. On the old continent, early 19th - century France is depicted in the pages of Victor Hugo's later Les Misérables. Wh ile words corne alive under the pens of Jane Austen, Mary Shelley, Stendhal and René Descartes, Géricault's << The Raft of the Medusa>> (1819) and Delacroix's <<Liberty guiding the people>> (1830) emerge as artistic masterpieces. Away from these creative heights, the lndustrial Revolution transformed Europe, whose borders were shaken by one man, Napoleon Bonaparte, self-proclaimed Emperor of the French in 1804. ln St. Barths, a sense of decline began to emerge from the 1820s onwards, following the glory of past yea rs. The early signs of an economic downturn manifested through the establishment of new trading posts and were further evidenced by a graduai decline in the population.

NYMAN URN

August Nyman, born in Stockholm on August 13, 1779, arrived in St Barths on July 9, 1802, to assume his role as a corporal in the garrison.

It was a remarkable twist of fate that his arrival coincided with the departure of the British, occurring just one day apart. The British, who had occupied St Barths since March 1801, bid farewell to Gustavia on July 10, 1802. Their departure left the island in a lamentable state, save for the remnants of the English fort constructed with the toil of enslaved individuals.

In the early 19th century, St Barths was engulfed in tumultuous circumstances. The young corporal, at the age of 23, swiftly found himself face to face with the stark realities of the situation. The Swedish garrison, typically consisting of approximately thirty soldiers, found itself reduced to merely a dozen capable men, among them the esteemed Nyman. In response to a raid by French privateers in 1807, a militia was established to bolster the weakened garrison.

On September 22, 1810, Governor Hans Henrik Ankarheim issued a directive for the disarmament of the civilian police force. The militiamen, under the leadership of influential merchants, were deeply angered by this decision, and their dissatisfaction swiftly transformed into a mutiny. It should be noted that the mutiny transpired rapidly within the military context, devoid of excessive force, casualties, or degradation.

The origins of this uprising remain somewhat obscure, unfolding in a unique backdrop. The Caribbean islands were heavily influenced by external events, overshadowed by the Napoleonic Wars and in the aftermath of the French and American Revolutions. Royalists and republicans vied for control of the colonies, the Haitian rebellion led by Toussaint Louverture fueled aspirations for freedom, and racial politics clashed with humanitarian ideals. Even within the small colony, the seeds of national identity were being sown. The process of naturalization was underway, yet the newly naturalized Swedes did not possess the same political rights as the native inhabitants. Frustration, self-interest, and loyalties collided with the inflexibility of the existing government. In addition, the insular nature of Gustavia, with its population of nearly 5,000 sailors accustomed to piracy, further contributed to the mutinous atmosphere.

Tensions simmer in the streets as the mutineers seize Commandant Bergstedt and make their way towards the Governor’s Mansion, where the reluctant captive, Ankarheim, remains confined.

Meanwhile, Samuel Fahlberg arrives at the battery of Fort Gustav III where he finds Sergeant Major August Nyman. According to the writings of Frank Olrog, «Fahlberg issued the command to load cannons and direct them towards the bustling town and its crowded main street. However, Nyman courageously defied these orders, convincing Fahlberg to reconsider. Thanks to his intervention, a potential bloodbath and the devastation of Gustavia were averted.. »

This version was always contradicted by S. Fahlberg, who claimed his innocence to the end. For some observers, Samuel Fahlberg, one of the first Swedes to reach the island, physician, secretary to the governor, surveyor, engineer, customs and finance inspector, director of the island’s land registry and survey, member of the Académie des Sciences and savior of a large part of the population thanks to a smallpox vaccination campaign in 1798, was the victim of a conspiracy. This central figure of St. Barths, who denied all the accusations against him, was exiled and sentenced to death for treason. He died on November 28, 1834 in St Eustache, unaware that he had been pardoned and rehabilitated a month earlier by the King of Sweden.

Due to his brave actions, August Nyman, who managed to prevent a massacre and, was celebrated as a hero not only within the town but also on the neighboring islands. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant. Unfortunately, Nyman’s life was cut short by enteritis, and he passed away on November 1, 1814. According to the Report of St Bartholomew of November 19, 1814, a collection was organized to honor the hero of 1810 with a monument. The funerary urn, executed by the renowned sculptor Johan Nicklas Bystrom, was first placed on August Nyman’s grave in the Public cemetery, then on a column at Fort Gustav III in 1817.

On one side of the marble urn, there is a bas-relief painting, decorated with two angels, which bears the following:

«August Nyman was brought here in 1814 by many friends different in language and color but united in their tears. It is beautiful to die here»

On the other side is an «allegorical figure representing the goddess of the West Indies». She wears a caduceus, and at her feet, a kneeling slave presents her with sugar cane. The caduceus, emblematic of medicine, also symbolizes commerce and eloquence. The top of the caduceus features a Phrygian cap (or liberty cap), well known to French and American revolutionaries as an emblem of liberty. The funerary urn, funded by the community («people from all walks of life in Gustavia contributed»),

was officially recognized as a Historical Monument in 1977. Additionally, in 1984, the street leading to Fort Gustav was named in honor of August Nyman.

SWEDISH SAINT BARTHS

In the 18th century, the Swedish desire for overseas territorial expansion began to materialize. Gustav III, who ascended to the Swedish throne at the young age of 26 in 1772, harbored the ambition of establishing a colonial empire in the Caribbean, aiming to elevate his country to the ranks of the renowned European colonial powers.

In the homeland, where the Ancien Régime held sway, society was built upon the pillars of privilege and authority, under the absolute monarchy ordained by divine right. However, winds of transformation were stirring, foreshadowing the imminent arrival of the French Revolution, while the reverberations of the concluded American War of Independence in 1783 still lingered. In that very year, in a di!erent realm altogether, the inaugural flight of a hot-air balloon graced the skies.

The destiny of Saint Barths was sealed in the halls of Paris. A pivotal agreement was inked on July 1, 1784, between Gustav III and Louis XVI, who still had his head at the time. France relinquished Saint

Barths to Sweden, in return for coveted warehousing privileges in the bustling port of Göteborg. A report from the same year provides some descriptive information about the colony:

«A Negro slave serves as doctor on the isle; he is trusted by everyone. He is said to be well-versed in bloodletting, fractures, and wounds. A European married in St Barths serves as writer, notary, etc., and settles the a!airs of the inhabitants. They are in the wrong hands as he is a drunkard... Three hundred bales of cotton are commonly exported from this island every year.»

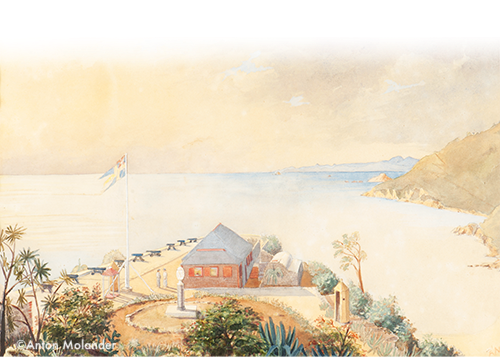

The island’s transfer of ownership commenced on January 30, 1785, as the Swedish vessel «Enigheten» arrived to claim its newfound territory. The o"cial moment arrived when the frigate «Sprengtporten», having embarked from Gothenburg on December 4, 1784, cast anchor in Carénage Bay on March 6, 1785. On board was Salomon Von Rajalin, the esteemed figure who would assume the role of St. Barths’ first Swedish governor. Among the passengers was Samuel Fahlberg, a notable individual whose presence would leave an indelible mark on the island’s rich history.

A fresh chapter unfolded, bearing the unmistakable imprint of the Swedish monarchy. With the stroke of a royal decree on September 7, 1785, the town was bestowed with a new name and heralded as a liberated port—free from tax burdens and welcoming all nationalities. This well-conceived economic endeavor garnered even the endorsement of Thomas Je!erson, who recognized St Barths as a valuable conduit for fostering commercial ties between Sweden and the United States. Moreover, it presented an opportunity to establish financial regulations on the slave trade, as enslaved individuals on the island were governed by the provisions of Sweden’s «black code» starting from 1787 onwards.

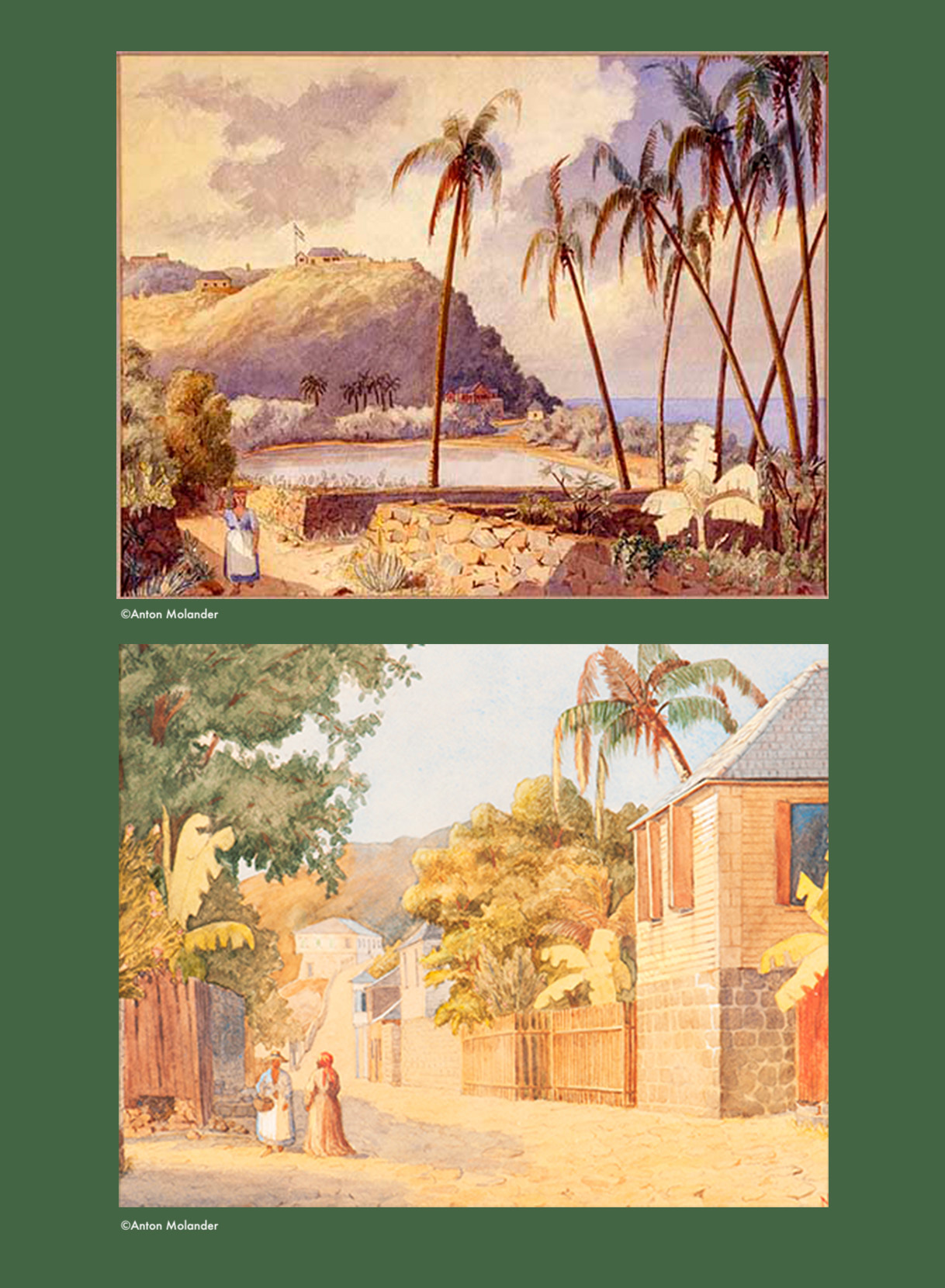

Gustavia, named after its monarch, emerges in lieu of Carénage, its streets meticulously laid and paved by enslaved laborers. Stone and wooden structures line these thoroughfares, while forts named Gustaf, Karl, and Oscar protect this land of promise. Steeples and churches reach towards the sky, anchoring the community with a connection to the divine.

The island, initially housing 749 residents upon the Swedish arrival, swiftly enticed newcomers with its free port designation, causing the population to double by 1786. Thriving commerce bestowed wealth upon individuals from all corners of the world. Gustavia’s harbor eagerly welcomed an increasing number of vessels from far-flung destinations, laden with valuable commodities for the new colony.

Saint Barths emerged as a pivotal trading hub in the Caribbean, witnessing an unparalleled economic surge.

This era, often referred to as the «golden age», stands in stark contrast to the backdrop of the French Revolution. In 1789, the storming of the Bastille preceded the Declaration of the Rights of Man, marking the demise of absolute monarchy. The two monarchs who had shaped the fate of St. Barths met tragic ends—one assassinated in Stockholm in 1792, the other guillotined in Paris in 1793.

The revolutionary fervor, which also reached the West Indies with Toussaint Louverture’s Revolt in Saint Domingue, seemed to have little impact on the island’s thriving economy. By the early 1800s, Gustavia alone boasted a population of nearly 5,000, ranking it as the sixth-largest city in Sweden. In 1800, St Barths was bustling with activity, housing 40 merchants, 3 dedicated grocery ships, 17 grocers, 2 insurance agents, 8 hotels and billiard halls, 22 establishments for quenching thirst, 6 bakers, 4 butchers, 3 jewelers, 1 watchmaker, 1 blacksmith, 8 masons, 7 shipwrights and 9 builders, 2 carpenters, 6 tailors, 3 shoemakers, and 1 hatter...

Uncertain tomorrows

After the glorious years, the island undergoes a gradual transformation, like a melodious tune fading into the twilight. The once abundant population declined inexorably, dropping from 4,394 souls in 1830 to 2,555 a decade later. Only a few meager exports still remain.

In town, where the blue and yellow flag flies, a kaleidoscope of nationalities rubbed shoulders at the start of the Swedish period. The alleys that came alive with stories from far away are, in the middle of the 19th century, a little more deserted. The buildings erected by the forced labor of slaves still testify today to the Swedish passage. In addition to buildings, cisterns were built to collect the precious liquid that falls from the sky.

In the serene countryside, the inhabitants piously confide in their Catholic faith, finding comfort there despite the shadows of apprehension and the veils of ingenuity that mingle around. The austerities that the Church could impose seem pale in comparison to the vagaries of everyday life. A life which takes on a certain simplicity, a happiness that knows no ambition. Everyone cultivates their garden, fishes, raises a few animals, and revels in the fruits offered by mother nature.

On October 9, 1847, on a memorable day, the infamous chains of servitude are finally broken in Saint Barthélemy: it is the abolition of slavery! The Swedish state buys back the freedom of the slaves who constitute at that date nearly 20% of the population. The island, lulled by this emancipation of historic significance, begins a new chapter in its destiny.

But disasters fall relentlessly, like a curse. Struggling with an undeniable economic decline, the island also has to face the fury of the cyclones which have swept through its regions in 1820, 1837, 1850, 1867, and 1876. Relentless droughts succeed one another. A dramatic epidemic of malignant fever, in the year 1840, mows down more than 300 souls, plunging the island into mourning and pain. Earthquakes, messengers of underground anger, shake Saint Barthélemy in 1843 and 1867. Finally, the Great Fire, an indomitable blaze, breaks out on March 2, 1852, in the direct vicinity of the Dinzey house. It reduces most of the southern area of Gustavia - now known as La Pointe - to ashes, bringing the city to its knees, and consuming 135 houses in flames. So many tragedies, harbingers of an inevitable outcome, are likely to shake the colony’s resilience.

In the late 1860s, when the last notes of the Swedish administration seem to fade away little by little, the distant crown, too overwhelmed by the financial burden of the island, tries in vain to sell it to the United States, to Prussia, then to Italy who would have liked to make it a penitentiary. But the course of fate does not follow this path.

In 1875 the island is reduced to 2374 souls. A vote, carrying an inevitable outcome, is proposed to the population, inviting it to decide on the return of Saint Barthélemy under the French flag. Only one voice, among the 351 expressed, is against this expected reunification. It is therefore the Retrocession, and hearts tighten when wishing goodbye to a bygone era.

On March 16, 1878, in an atmosphere of melancholy, the Swedish flag is lowered, marking the end of the Swedish era on this island. The last Swedes will leave aboard the frigate Vanadis on March 20, 1878, leaving behind them memories and stories forever engraved in the minds.

And so, ends a chapter of history, while another, new, will be written with the ink of promises and challenges to come.

Opening Hours

Monday : Closed

Tuesday Wednesday Thursday : 8h30 - 12h45 15h-19h30

Friday : 8h30 - 12h45 15h - 19h30

Saturday : 8h30 - 13h