THE FIRST SAINT-BARTH PEOPLE

In a world that expands with each new revelation, St Barths appears destined to endure in its tranquil, perhaps even abandoned state... but for how long?

The initial colonizer to create a stir upon arrival was Pierre Belain d’Esnambuc.

Driven by ambition and possessing remarkable diplomatic skills, Pierre Belain d’Esnambuc, a privateer turned colonizer, arrived in St. Christopher (now St. Kitts) in 1625 with the intention of rebuilding his fortune. The island, already occupied by the English under Warner’s leadership, would serve as a vital base for the colonization of several islands in the Lesser Antilles, including St. Barths. After returning to France in 1626, d’Esnambuc came back to St. Christopher a year later as the governor of the newly established “Compagnie de St. Christophe”. This company was formed under the influence of its main shareholder, Cardinal Richelieu.

By mutual agreement - a unique treaty ensuring Franco-British non-aggression, even during official wars - the French, English, and Caribs coexist on the island of St. Christopher. The atmosphere is tense yet stable, shaped by rivalries and differences. Although there is a relative peace, the indigenous people have devised an extensive plan, mobilizing approximately 4,000 Caribs from neighboring islands with the sole objective of eradicating all the present settlers. However, thanks to the betrayal of a Caribbean woman who shared d’Esnambuc’s bed and alerted him, our story took a different turn. The French and English successfully repelled the Caribs in a violent clash, thwarting their malevolent intentions.

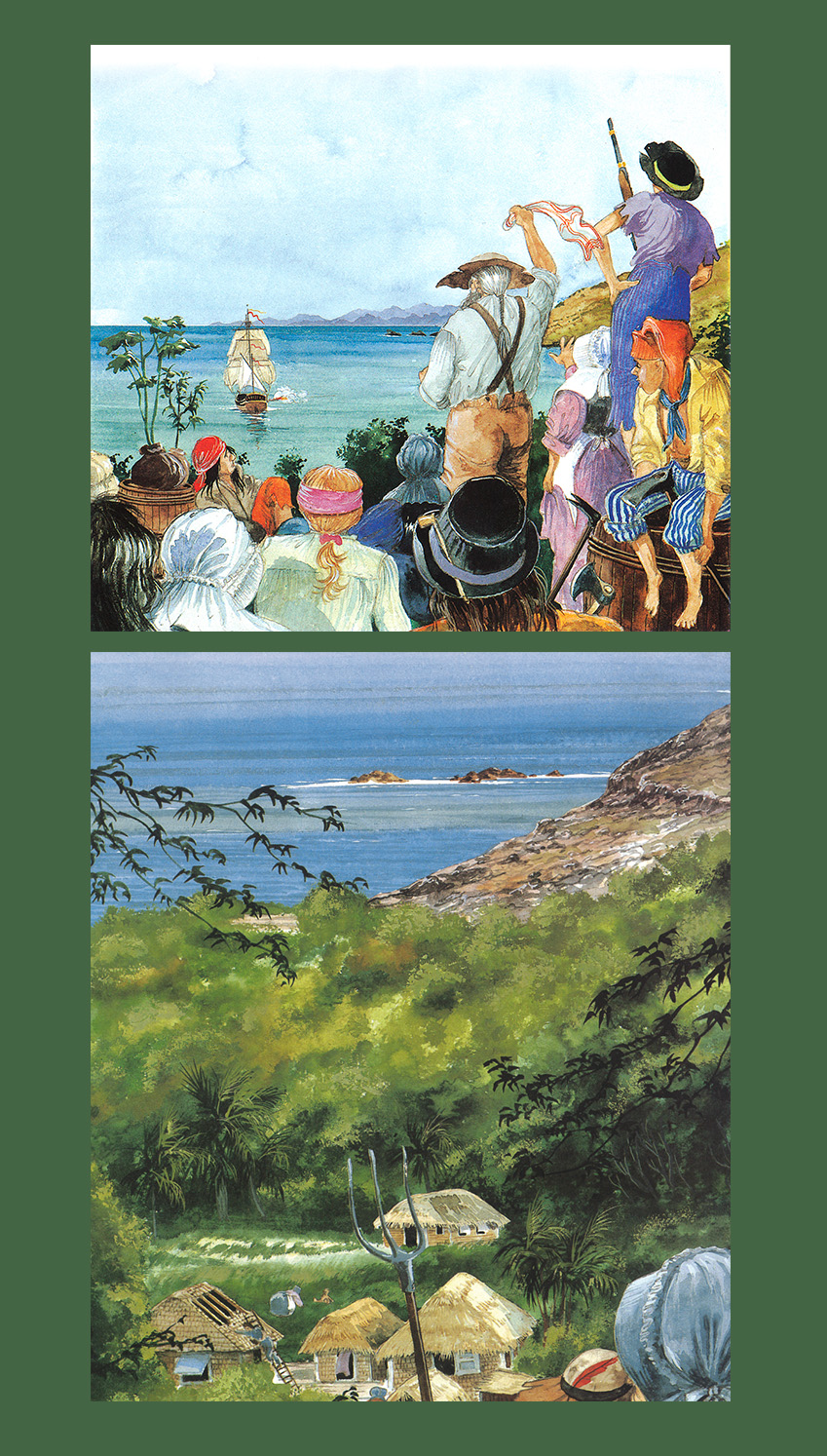

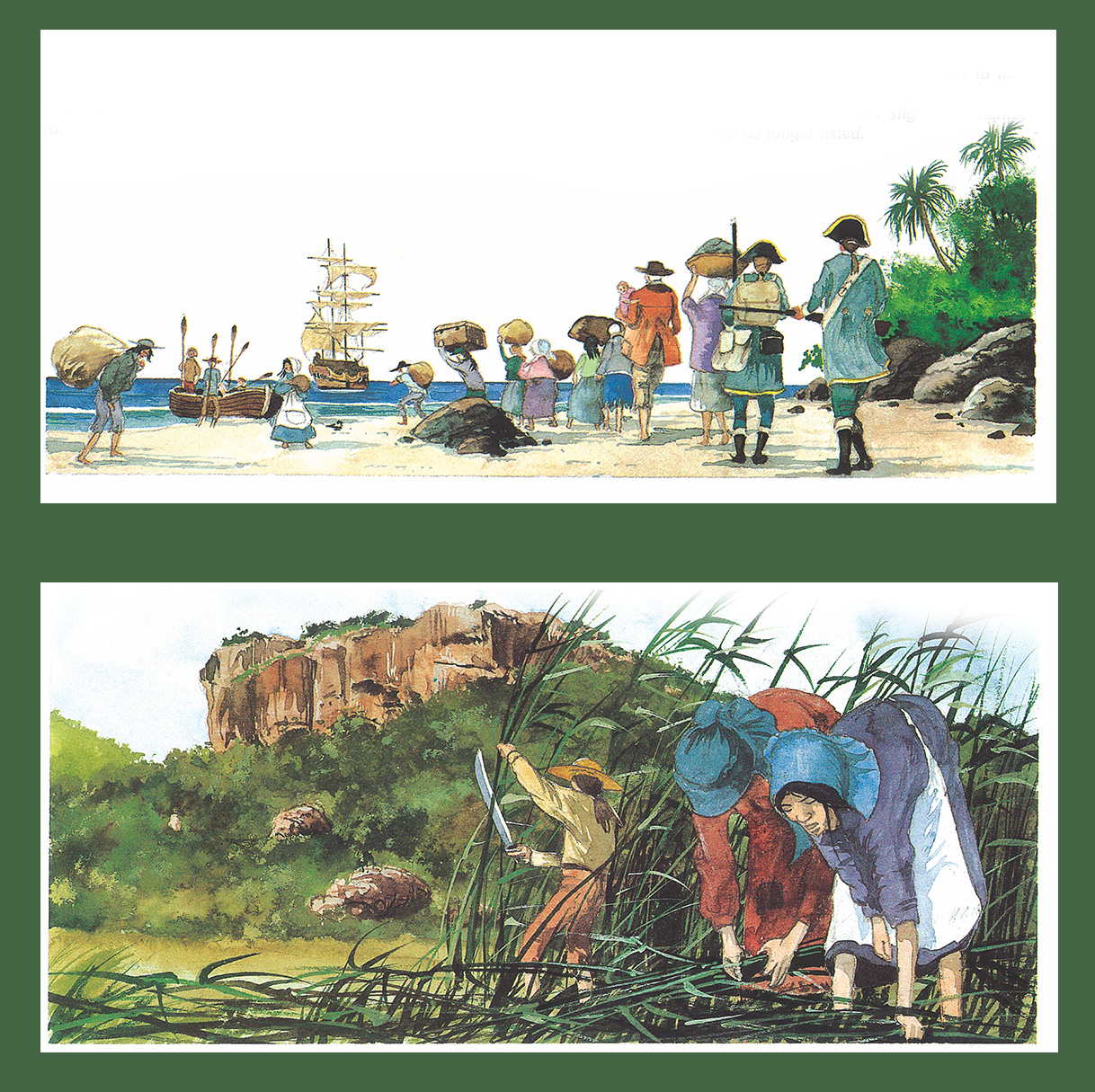

The colonies, adorned with fleur-de-lys and leopards, experienced a brief respite with the intervention of the Spanish. Eager to cleanse the «cays» of privateers and pirates, the Spaniards commanded the evacuation of all the inhabitants of St. Christopher. This took place in the year 1629! It was during this event that d’Esnambuc made the decision to leave a handful of men on the small island of St. Barths. This significant date marks the arrival, although temporary, of the first European settlers on St. Barths. They were French and their enthusiasm for this petite «rock» was rather limited, as much work lay ahead despite the island’s undeniable charm!

Upon the Spanish departure, d’Esnambuc swiftly brought back all his exiles to St Christopher. This was followed by challenging years that ultimately led to the dissolution of the Compagnie de St Christophe. Sensing the need for more resources to fulfill his grand aspirations, Cardinal Richelieu, known for his shrewdness, established the Company of the Islands of America in 1635. This new company not only eased Governor d’Esnambuc’s responsibilities but also facilitated trade, particularly the export of cultivated tobacco, with France.

Meanwhile, the uninhabited St. Barths returned to its monotonous state, occasionally disrupted by the arrival of pirates, privateers, corsairs, and buccaneers, who found solace in the secluded bay of Carénage (now Gustavia).

After the death of d’Esnambuc, succumbing to syphilis in 1637, the commander of the Order of the Knights of Malta, Philippe Longvilliers de Poincy, assumed the position of Lieutenant General of the Isles of America in 1639. According to Du Tertre, he strategically decided to occupy St Barths in 1648 and sent Jacques Gante with 52 men for a settlement intended to be permanent. The same year marked the end of the «Thirty Years’ War» in Europe and the beginning of the Fronde in France.

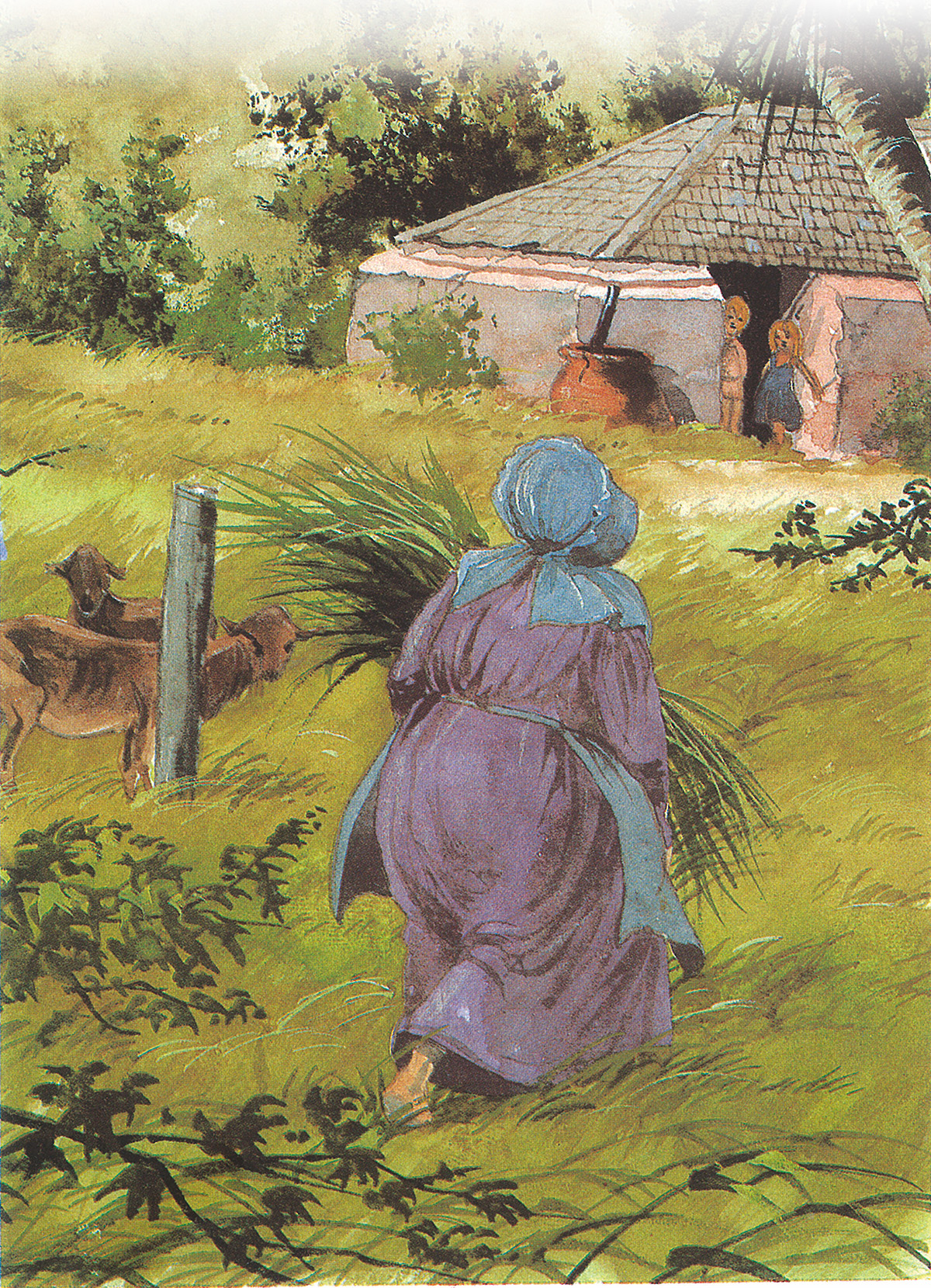

However, these were not major concerns for this new island community, as they had much to do to ensure their survival. In great destitution, guided by Gante and Mr. Bonhomme, these men began their settlement and planted mango trees, lemon trees, orange trees, and breadfruit trees in the arid soil of St Barths. The island, undoubtedly less dry and more wooded than it is today, also allowed for the cultivation of cassava, yams, malanga, and exportable goods such as indigo or tobacco.

In 1651, the financially strained French company, facing the Spanish threat, made the decision to sell its territories to the Order of the Knights of Malta. The Order retained Commander de Poincy as the leader of St Martin (half) and St Barths until his passing in 1660. This event is the reason behind the presence of the Knights of Malta’s cross in the center of St Barths’ coat of arms today.

St. Barths continued its development, unaffected by the distant affairs of the powerful. In 1653, with just 200 inhabitants, their sole wealth was the abundance of coconut palms. They yearned for peaceful days, but their hopes were shattered on a tragic night. According to certain accounts, the previously discreet Carib people launched a sudden attack, massacring the colony of St Barths in 1656, after departing from St Vincent and Dominica. It is said that the severed heads were displayed on spikes as trophies and a show of intimidation on Lorient beach. The few survivors of the brutality fled to St. Martin and St Christopher, once again leaving St. Barths deserted.

It wasn’t until peace was established with the Caribs in 1660 and the resilience of de Poincy that St Barths, now inhabited by a small group of settlers, began to rise from the ashes. The task was arduous, and life under the sun was no less challenging.

Meanwhile, King Louis XIV, the 14th of his name, was engrossed in constructing a residence unlike any other on his Versailles estate, where grandeur and opulence vied for the admiration of courtiers.

In 1665, the same year St. Barths was repurchased from the Order of Malta by the West India Company, Father Dutertre noted around a hundred individuals residing on the island. These men, hailing mostly from western and southern France, bore names such as Aubin, Bernier, Gréaux... They were not saints, and by choosing to settle in St. Christopher and later in St Barths, they had, in some cases, distanced themselves from the debts, galleys, or gallows that awaited them in Europe. Thus, the tale of the first St Barth people began!

THE SETTLEMENT OF ST. BARTHS

We find ourselves in an era when ships traversed the oceans, explorers sought uncharted territories, and European powers engaged in global conflicts. It was the 17th century, and the settlement of Saint Barths was just beginning to take shape. According to the accounts of early chroniclers, the living conditions were incredibly challenging. Only the most resilient individuals - and they were indeed resilient - held on to this inhospitable land with an unwavering determination to stay. In 1671, the initial population count documented 85 household heads, 3 widowed household heads, 47 married women, 53 boys, 43 girls, 15 skilled servants, 8 white servants, 36 servants, 25 black men, 15 black women, and 6 black children, making a total of 336 residents, with 290 of them being white. Approximately 45% of the Estate owners were single individuals. Slaves, who had been present since the early days of settlement, constituted a minority and labored alongside the white inhabitants in tending the land. While their existence did not grant them freedom, the circumstances on St. Barths were undoubtedly distinct from those on neighboring islands. With a herd consisting of 16 oxen, 60 cows, 25 calves, and a lone donkey, St Barths aspired to further development, even in the face of a cruel absence: water. This modest growth resulted in a relative increase in the population. In 1681, there were 379 inhabitants, followed by 410 the next year, and 448 in 1686. In the official census conducted on July 18, 1681, we encounter names that still resonate today, intertwining with more contemporary ones, like Corosol, Vitté, and Pierre Legrand, which have transformed into street names, marking specific locations. We also find surnames such as Aubin, Bernise (possibly Bernier), and Greau (in the singular form?), whose spelling may have undergone changes over the centuries, yet remain relevant in the 21st century. Towards the conclusion of the decade, additional names emerged, including Questél, Laidé, de Laplace, Devé, Berniér, and Gruau, adding to the tapestry of identities in the community. By the close of the 17th century, the censuses encompassed a diverse range of individuals: men and boys ready for military service, indentured servants, young girls to be married, widows, religious individuals, disabled people, mulattoes, Black men, women and children, girls over 12 years old, nubile young women, slaves, enslaved natives, elderly men unfit for service, and more. These criteria, deemed unacceptable in present-day society, likely evoked minimal commentary or criticism during the early days of the Enlightenment era. Between 1681 and 1765, the population saw a small decline, settling at approximately 448 to 371 residents. Influenced by their origins in the mother country, particularly from the western regions, the islanders have maintained their cultural heritage. This is evident in the use of stone walls to demarcate land parcels, the preservation of traditional attire such as the horse-drawn carriage (also associated with the traditional headdress), and the continuity of language, including specific phrases and intonations that have remained unchanged over time. In 1744, the island fell under English control as they accused it of providing shelter to French privateers targeting their vessels. During the attack, the English privateers pillaged St Barths, causing extensive damage to guaiac trees, cisterns, and wells, with only a small group of around thirty survivors remaining. The majority of the population was deported, but their resilience was unwavering, and they persisted in returning to the island. According to later censuses, the population expanded to 749 individuals by the start of 1785, coinciding with the arrival of the Swedes to the island. In the midst of these turbulent times, the Saint Barth people encountered numerous challenges. Caught in the crossfire of global conflicts like the Seven Years’ War and the League of Augsburg, plagued by maritime raiders, or simply weary of the daily struggles, some individuals opted for exile. Nevertheless, despite the challenges, their unwavering attachment to their homeland prevailed. Their hearts pulsated for this small, unforgiving island, battered by storms, which held a special place in their hearts. They came back, reclaiming what was rightfully theirs. And thus, despite the unpredictable turns of history, Saint Barths remained their cherished possession. A rugged and invaluable gem, shaped by the diligent hands of its courageous sons and daughters.

Illustrations by M.Stanislas Defize and taken from the book Histoire de St-Barth

Opening Hours

Monday : Closed

Tuesday Wednesday Thursday : 8h30 - 12h45 15h-19h30

Friday : 8h30 - 12h45 15h - 19h30

Saturday : 8h30 - 13h