At first, there was an island !

For ages, St. Barths stood unaltered, molded solely by nature, still nearly pristine as its inception.

A fragment of a forgotten Eden, tenderly embraced by trade winds, immersed in the azure hues of sky and ocean. Within, a realm of sandy shores and swaying coconut trees, radiance, tranquility, and delight. A realm that cherishes simplicity! Or does it?

In an epoch perhaps within the 12th or 13th century, a voyage was undertaken by the Caribs, embarking from the northern shores of South America, propelled by the force of their paddles. Their course guided them to the Lesser Antilles, where an inhabitation already thrived, nurtured by other Amerindians—the Arawaks (comprising diverse tribes such as the Igneris, Taïnos...). These dwellers embraced a way of life reliant upon the bounties of fishing, hunting, and gathering.

Within the writings penned by explorers and early settlers, a prevalent trend emerges, one that idealizes the serenity of the Arawaks while simultaneously portraying the Caribs as savage beings, skilled in the art of barbarism and cannibalism. Yet, it is imperative to bear in mind that this reputation, not only of the Caribs but of all Amerindians, originates from the perspective of so-called civilized Europeans, encountering what they deemed as savage natives. The lens through which these tales unfold is unavoidably colored by the cultural background of the storytellers and the justification of colonialist agendas, rendering it an imperfect reflection of reality at that time.

Despite our limited understanding of these Amerindian communities, there exist words and linguistic fragments that resonate with familiarity. Take, for instance, coulirou, balaou, hamac, maboya, colombo, and countless others, seamlessly integrated into the lexicon of modern-day Creole and French, bridging the past with the present.

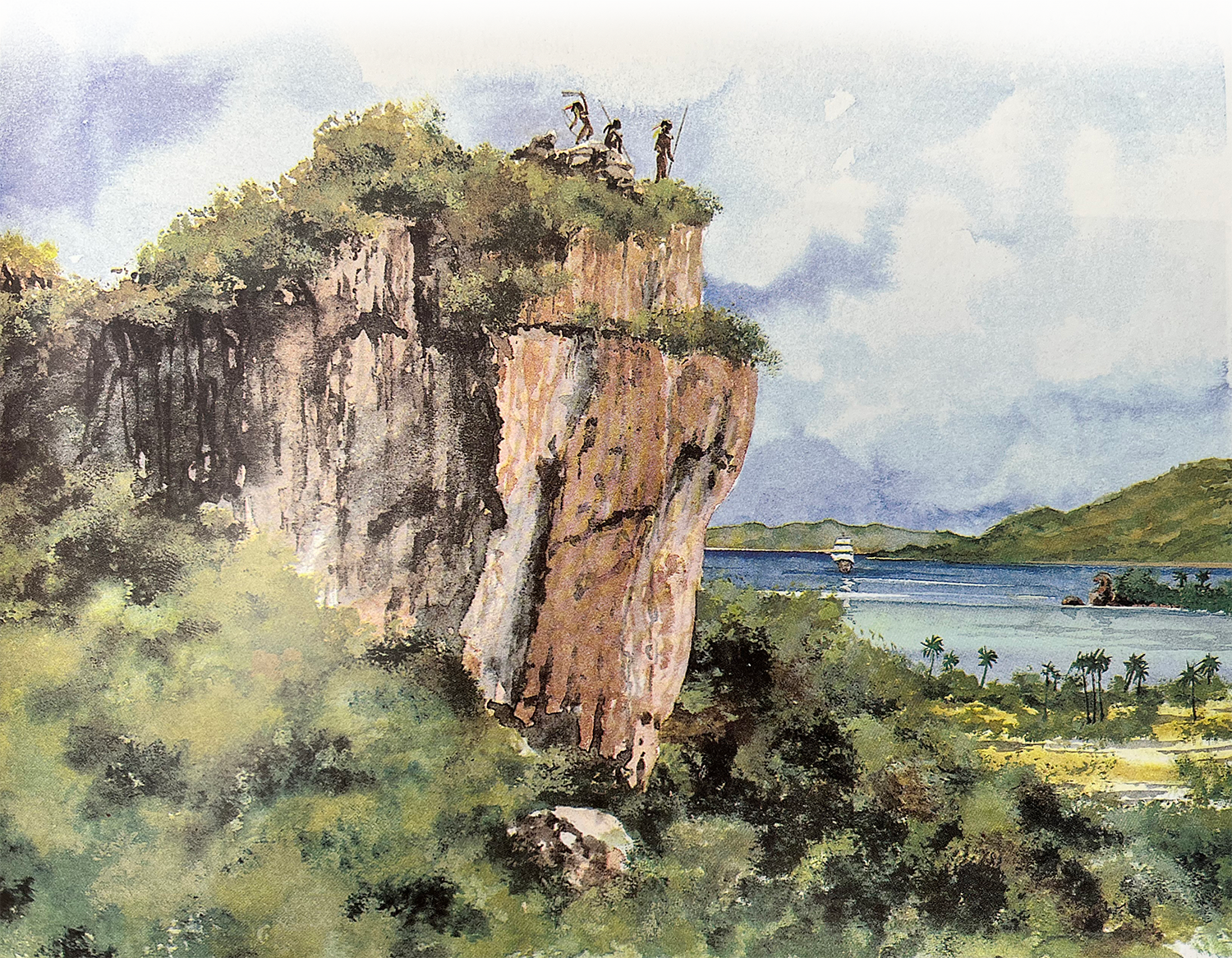

As chronicled by diverse accounts, the Caribs garnered a reputation for their unwavering defiance against European intruders, celebrated for their navigational prowess, and dreaded for their alleged cannibalistic tendencies. The island became a strategic hub for their belligerent and trade-driven ventures.

Consensus holds that the small island of St. Barths, burdened by scarcity of fresh water and inhospitable soil, remained unpopulated for an extensive span. However, it became a frequent destination for indigenous peoples, who made brief stops to procure meager provisions from sporadic supplies or nature’s frugal offerings. Engaging in activities such as lambis fishing, hunting the iguana, extracting milk from manchineel trees to coat their arrows, and fashioning robust «boutous» from plentiful guaiac wood, these seasoned seafarers transformed the island into a vital layover. Their seafaring journeys were undertaken aboard sturdy long boats hewn from tree trunks.

Once known as «Ouanalao,» the island drifted through the currents of antiquity and the Middle Ages, leaving no lingering marks upon historical records. As the threshold of modernity emerged, Christopher Columbus, embarking on his second voyage to the West Indies, chanced upon this land. Though not uncommon to unveil a place already touched by prior visitors or dwellers, Columbus bestowed upon it a new name—San Bartolomeo—paying homage to his brother. This significant event unfolded in the year 1493.

Meanwhile, as the Renaissance blooms across the old continent, bringing forth a reawakening of arts and letters, our remote and untamed archipelago remains oblivious to its enchantment. Around 1505, Leonardo da Vinci immortalizes the Mona Lisa with his brush, while Michelangelo crafts his timeless masterpiece on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the subsequent decade. These magnificent creations, treasures of humanity now deemed invaluable, emerge in complete indifference. No instant snapshots shared on «Insta,» no messages carried by humble carrier pigeons. Quite nobody on the island of San Bartolomeo.

Illustrations by M.Stanislas Defize and taken from the book Histoire de St-Barth

Opening Hours

Monday : Closed

Tuesday Wednesday Thursday : 8h30 - 12h45 15h-19h30

Friday : 8h30 - 12h45 15h - 19h30

Saturday : 8h30 - 13h